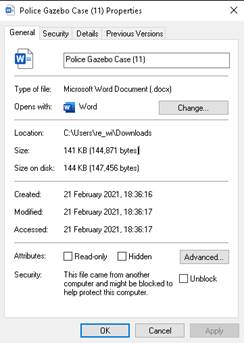

Some time when I use my windows

10 computer, I cannot get the links to open in word after download, how to

resolve.

Method 1

Go to your download location and

right click on the file then go to property’s afterwards click on unblock “next

to read only and hidden.”

Method 2

Complete fix for all files

https://appuals.com/fix-this-file-came-from-another-computer-and-might-be-blocked/

If you click on a Docx file and

Word just opens with an error, check in you download location and following the

instructions above!

--

https://serverone.hopto.org/accpersonpowers%20Community%20Officers%20Si%20Mod/

https://serverone.hopto.org/Community%20safety%20accreditation%20scheme%20Si%20Mod/

https://serverone.hopto.org/Police%20community%20support%20officer%20Si%20Mod/

https://serverone.hopto.org/Police%20Reform%20Act%202002%20Si%20Made/

Still to fix

Audio Files

https://serverone.hopto.org/Audio%20Files%20Link/

If you click on a Docx file and

Word just opens with an error + you can’t see the download link, check in you

download location on your pc and following the instructions above!

P.s Use

the Index file for an Index

TABLE OF UK CRIMINAL OFFENCES

TABLE OF UK OFFENCES

https://www.horrificcorruption.com/some-uk-laws-an-indexed-table

Maximum Sentences for Criminal

Offences Table List

https://www.thelawpages.com/court-cases/maximums.php

Magistrates’ Court Sentencing

Guidelines

https://www.sentencingcouncil.org.uk/offences/

|

Suitable for Press? |

Yes www.Horrificcorruption.com

home page and any other gazette. 13/03/2021 |

Intentional or Reckless Sexual

Transmission of Infection

https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/intentional-or-reckless-sexual-transmission-infection

Ø The

Enfield Council “I

put an FOI in and am waiting for 2021 policy & all underwriting of all the

policies” Enfield council hired DAC Beachcroft see audio files below Index

folder for more information. (1)

Enfield Letter 27.08.19 Insurance

details and claim process MR S CORDELL (2)

Enfield Insurance Incident report

form 2013 - 2020 https://serverone.hopto.org/Enfield%20Insurance%20Incident%20report%20form%202013%20-%202020/ Ø

The Metropolitan Police Force 2012 “I am going to put an FOI in for the

policies” 11/03/2021 (1)

Police policy 2012 https://serverone.hopto.org/Police%20policy%202012/ (2)

Police PL Primary summary 2012 https://serverone.hopto.org/Police%20PL%20Primary%20Summary%202012/ (3)

Police PL Excess layer Swiss 2012 https://serverone.hopto.org/Police%20PL%20Excess%20layer%20Swiss%202012/ (4)

Published

items https://www.met.police.uk/foi-ai/af/accessing-information/published-items/?q=insurance (5)

Published

items Personal Insurance Indemnity - Policy https://serverone.hopto.org/Police%20Zurich%20personal-insurance-indemnity---policy/ (6)

Published

items Information Rights Unit MPS Insurance

2019 https://serverone.hopto.org/Information%20Rights%20Unit%20Mps%20Insurance%202019/ (7)

NHS Resolution = All Doctors and

GPS (a)

01m. Mental Health Resolution (2) 04

11 2019 aaaaaaaaaa.WMA (b) 01m. Mental Health Resolution (3) 04

11 2019.WMA (c)

01m. Mental Health Resolution (4) 04

11 2019.WMA (d) 01m. Mental Health Resolution (6) 04

11 2019.WMA (e)

01m. Mental Health Resolution (7) 04

11 2019.WMA NHS

Insurance Info dh_117480 https://serverone.hopto.org/NHS-Indemnity/ NHS-Indemnity https://serverone.hopto.org/NHS-Indemnity/ NHS

Resolution “Direct Link” Member

of Parliament UK http://www.w4mp.org/w4mp/w4mp-guides/your-office/insurance-for-mps/ Member

of Parliament UK -Handbook – Insurance Page 40 = intranet.parliament.uk/insurances https://serverone.hopto.org/Member%20of%20Parliament%20Uk-handbook/ MPs FOI

Information https://www.parliament.uk/site-information/foi/ MPs Office Costs Quick

Guide_2.pdf Employers\xd5 Liability

Insurance Bureau Bill (parliament.uk) Enfield

Neighbourhood Team Insurance Details Letter of Claim PLEASE DO NOT IGNORE THIS

EMAIL. BELOW IS A DRAFTE D LIST OF

PARTICULARS OF MY CLAIMS. WHAT ARE FOR AN AMICABLE SETTLEMENT (OUT OF COURT)

DUE TO INCIDENTS THAT THE LISTED BELOW ARE VICARIOUSLY LIABLE FOR. I

Mr. Simon Cordell have gotten asked to clarify why I am lodging insurance

claims against the listed companies and civilians. This

is not a conclusive summery of the Listed -- Listed Number 1 of 5 Company & Branch The Enfield Council Dates; From 2013 till date of 25/01/2021 Team Members Names 1. 2. 3. 4. Notes; (a) The

Forged Asbo “Held

responsible” Dates (b) The Forged

Possession Order 1 “Held

responsible” Dates (c)

The Forged 1st Injunction Order “Held responsible” Dates (d) The

Forged 2nd Injunction Order “Held

responsible” Dates (e)

The Forged Possession Order 2 “Held responsible” Dates ----- Listed Number 2 of 5 Company & Branch The Enfield Homes Dates; From 2006 till date of 25/01/2021 Team Members Names 1. 2. 3. 4. Notes; Ø Housing

disrepair = (Right to Repair) “Held responsible” ----- Listed Number 3 of 5 Company & Branch The Enfield

Neighbourhood Watch Dates; From 2013 till date of 25/01/2021 Team Members Names 1. 2. 3. 4. Notes; (a) The

Forged Asbo “Held responsible” Dates (b) The

Forged Possession Order 1 “Held responsible” Dates (c) The

Forged 1st Injunction Order “Held responsible” Dates (d) The

Forged 2nd Injunction Order “Held responsible” Dates (e) The

Forged Possession Order 2 “Held responsible” Dates ----- Listed Number 4 of 5 Company & Branch The Metropolitans Police Constabulary’s Edmonton

and Woodgreen Dates; From 2013 till date of 25/01/2021 Team Members Names 1. 2. 3. 4. Notes; (a) The

Forged Asbo “Held responsible” Dates (b) The

Forged Possession Order 1 “Held responsible” Dates (c) The

Forged 1st Injunction Order “Held responsible” Dates (d) The Forged

2nd Injunction Order “Held responsible” Dates (e) The

Forged Possession Order 2 “Held responsible” Dates ----- Listed Number 5 of 5 Company & Branch The Enfield, Barnet & Harringay Mental Health

Unit “The Enfield Team Dates; From 2013 till date of 25/01/2021 Team Members Names 1. 2. 3. 4. Notes; ---- Re:

myself: -- Mr. Simon Paul Cordell LETTER

OF CLAIM I ‘am as named above am making this

claim in regards to; Damages As

I can prove the Listed 1,2,3,4,5 companies’ staff have acted (a)

Bios and unreasonable while taking on

running companies’ activities in the public domain. (b) Them

involved staff have caused and are causing a Poor reaction times to public

concerns. (c)

Negligence (d) Gross

Misconduct (e)

A large amount Criminal Offences And

in a knock-on effect their reckless behaviour has caused me to suffer by ways

such as; General

damages = General damages relate to the impact

on my life when referring to such issues as: (a)

Pain and suffering caused by the

Listed 1,2,3,4,5 (b) Forced

changes to my lifestyle. (c)

Mental trauma. Special

damages = Special damages relate to the impact

on my life when referring to such issues as: (a)

Loss of earnings. (b) My

future loss of earnings. (c)

Medical treatment. (d) Future

medical treatment. (e)

Transport expenses relating to forged

court case (f)

Changes to my living environment. That are in connection with; (1)

Joint Enterprise / Joint Circular (a)

Joint Enterprise Ø Demeanour (a) Joint

enterprise is a doctrine of criminal law which permits two or more defendants

to be convicted of the same criminal offence in relation to the same

incident, even where they had different types or levels of involvement in the

incident. (b) Is

joint enterprise still a law UK? In

February 2016, the court ruled in Jogee's favour,

resetting the law of joint enterprise. Ø Law Charging

group assaults Where

a death or serious assault occurs at the hands of a group or gang,

prosecutors should seek to determine the exact role played by each suspect

and select charges that differentiate the roles. However,

prosecutors should be mindful, when selecting charges, not to overly

complicate the presentation of a case. This includes a consideration of the

directions of law that the indictment will require as a result. In

homicide cases, it is not always possible to identify who are the killer(s)

or principal offender(s) and who are the secondary parties. R v Jogee confirms that it is not necessary to prove

whether a defendant is a principal or an accessory [88] (provided he is one

or the other), and in a multi-handed assault it will often be the case that

no-one can say whose hand did the act which proved fatal. What is necessary

is that someone (identified or not) is shown to have committed murder or

manslaughter. In

such cases, it is permissible to prosecute the participants to the offence as

principals, without necessarily differentiating roles. However, alternative

charges may be put on the indictment, to allow the jury to convict D of a

lesser offence, where it is not satisfied that D was responsible for the more

serious offence. Ø Secondary

Liability Under Subsections (a) and (c) of Rule 10b-5 Key

Points: • The Court held that a defendant’s act of sending

emails drafted by another, that the defendant understood to contain material

untruths, was sufficient to establish that the defendant employed a “device,”

“scheme,” or “artifice to defraud” or an “act, practice or course of

business” that “operates ... as a fraud or deceit” under Rule 10b-5(a) and

(c), § 10(b) of the Securities Exchange

Act, and § 17(a)(1)

of the Securities Act. • The Court’s decision has implications for any party

involved in the “dissemination” of information to investors, regardless of

whether he or she “made” the statement. This is of particular

significance to bankers and other investment professionals who may “cut

and paste” the statements of others. However, the decision does not

affect the requirement that to be liable for securities fraud, the person

disseminating the information must have intent to defraud. • The Court noted

that its 2011 Janus1 ruling may remain relevant (and preclude liability) if

“an individual neither makes nor disseminates false information — provided,

of course, that the individual is not involved in some other form of fraud.”

• The Court recognized that applying Rule 10b-5(a) and (c) may “present

problems of scope in borderline cases,” creating the likelihood of intense

factual inquiry in lower courts. Ø The securities exchange act of 1934 “USA” The Securities

Act of 1933 was the first federal legislation used to regulate the stock market. ... The Securities Act of 1933 is governed by the Securities and Exchange Commission, which was created a year

later by the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Ø Accessories

and Abettors Act 1861 “UK” The

starting point is at Section

8 of the Accessories and Abettors Act 1861. This provides that

whoever shall aid, abet, counsel or procure the commission of any indictable

offence shall be liable to be tried, indicted and punished as a principal

offender. Historically the position at common law was that aiders and abettors

were said to be principals in the second degree and were actually or

constructively present at the time the offence was committed by the

principal. By contrast, counsellors and procurers were accessories before the

fact whose presence at the time of the offence was not necessary. The current

position is that the four varieties of conduct overlap and they cover any

form of assistance or encouragement. (The position in relation to summary

offences is governed by the Magistrates' Courts Act 1980,

section 44, which is in all material respects identical to section 8.) Ø It

has been held by the Court of Appeal that there is no violation of Article

6(3) of the European Convention on Human Rights when the prosecution alleges

that D is party to an offence but cannot specify his precise role: R v.

Mercer [2001] EWCA Crim. 638. Ø In

the case of joint enterprise liability, D and P embark on a joint venture to

commit an offence, and, in the course of the joint venture, P commits another

offence. For example, D and P agree to commit burglary. If P commits the

offence while D acts as a lookout, no difficulty arises. But what if P

commits another offence which is in addition to or instead of the agreed

offence? For example, D and P agree to commit burglary. They are disturbed by

the householder; V. D knows that P is armed with a knife. P uses the knife to

stab and kill V. D is guilty of murder if he foresaw that P, as an incident

of the joint venture might commit that offence: Chan Wing-Siu [1985]

A.C. 168; Powell and Daniels [1999] 1 A.C. 1. The rationale for the

joint enterprise liability rule is that D, by attaching himself to the

venture to commit one offence, consciously accepts the risk that a

co-adventurer might commit another offence. Ø D's State of Mind in Relation to The Commission of The Offence By P In Johnson v. Youden [1950] 1

K.B. 544, Lord Goddard C.J. said: "Before a person can be

convicted of aiding and abetting the commission of an offence, he must at

least know the essential matters which constitute the principal offence."

This statement of principle was subsequently approved by the House of Lords

in two cases: Churchill [1967] 2 A.C. 224

and Maxwell [1978] 1 WLR 1350. It is therefore necessary to establish what is

meant by the "essential matters" and what is meant by "know." In their report on secondary participation, the

Law Commission concluded that the essential matters are fourfold: (a)

D must "know" that

P is going to do an act which satisfies the conduct element of the offence

(but not necessarily the details of the act). (b)

D must "know" of

the circumstances necessary to constitute the offence. (For example, D sells

P a hammer believing that P will use it to cause damage to property belonging

to P. One circumstance that must be present in the offence of criminal damage

is that the property belongs to another person. If P uses the hammer to

damage property belonging to V, D is not guilty, as a secondary party, to P's

offence of causing criminal damage.) (c)

As a general rule D must "know"

the consequence element of the offence. But an exception arises if the

principal's liability for the consequence is 'constructive.' For

example, D assists P to assault V. Both D and P intend to cause V only minor

harm. P hits V and V falls over and dies. P is guilty of manslaughter. So too

is D. (d)

D must "know" that

P will act with the fault element required in relation to the principal

offence. For example, D assists P to appropriate property belonging to

another. P does so dishonestly and with an intention permanently to deprive

that other person of the property. D is guilty as a secondary party if he 'knew'

that P would act with that state of mind. Ø 'Knowledge'

The Law Commission concluded that the requirement of knowledge

is satisfied if D knows or believes that:

(a) P is committing or will

commit the conduct element of the offence; (b) P is doing or will do so in

the circumstances and with the consequences, proof of which is required for

conviction of the offence. As

the Law Commission noted, despite what was said by Lord Goddard in Johnson

and Youden and

despite the fact that that case was approved by the House of Lords on two

occasions, there are decisions of the High Court and the Court of Appeal

which appear to dilute the requirement of knowledge. These cases provide some

support for four possible tests: (a) D must believe that P would

or might commit the conduct element of the offence: Blakely

& Sutton v. Director of Public Prosecutions [1991]

RTR 405; (b) D must foresee the risk of a

strong possibility that P will commit the offence: R v. Reardon [1999]

CLR 392; (c) D must contemplate the risk

of a real possibility that P will commit the offence: R v. Bryce [2004]

EWCA Crim. 1231; (d) D must foresee that it is

likely that P will commit the offence: R v. Webster [2006]

EWCA Crim. 415. Ø The Serious Crime Act 2007 The common law principles relating to secondary party liability must

now be read together with the Serious Crime Act 2007, which came into effect

on 1st October 2008. The

2007 Act creates three new offences: (a) Intentionally

encouraging or assisting an offence (section 44); (b) Encouraging

or assisting an offence, believing it will be committed (section 45); (c) Encouraging

or assisting offences, believing one or more will be committed (section

46). Ø Penalty Ø Joint

Enterprise (b) Joint

Circular Ø Demeanour Ø Law Ø Penalty ·

Temp Location for Now Ø INDEX (A)The 1st

Asbo Folder 1st Index Original (B)1ST

Asbo Folder “For Magistrates Court Highbury” (C)Asbo “Rip

apart File” (D)The 2nd

Asbo Folder 1st Index Original (E)2nd

Asbo Added Bits Only in the Appeal Stage1 (F)2nd

Asbo Folder “For Crown Court Woodgreen” (G)XXXX (H)The

Prosecutions Skeleton Argument is not INDEXED (I)The

Prosecutions Skeleton Argument “For the Asbo” (J)My 1st

Asbo Response Bundle INDEX (K)My

Response Bundle “For the Asbo” (L)1st Housing

Possession Order Book INDEX (M)Email Book

Walking to the 1st Housing Possession Order INDEX (N)1st

Possession Order “Dated: 19th July 2017” (O)The

1st Injunction Order INDEX (P)1st

Injunction Order Statements Getting Ripped (Q)1ST

Injunction Order Dated: 10/08/2017 (R)The

2nd Injunction Order INDEX (S)The

2nd Injunction Order Statements Getting Ripped (T)2nd

Injunction Order (U)The 2nd

INJUCTION FOLDER INDEXED Original made by Enfield Council When Ordered to by

the Judge Original (V)All in One

2nd Injunction Order Judge Indexed (W)2nd

Injunction Order “Indexed by Order of the Judge” (X)A Second

Housing Possession Order Served & Dated: 06/02/2019 Till 10/06/2019 INDEX (Y)2nd

Possession Order (Z)Freedom

of Information “Enfield Councils Computer System - Index” (AA)Freedom

of Information “Enfield Councils Computer System” (BB)Doctors

NHS & Private “RIO” INDEXED (CC)Freedom

of Information “NHS Computer System” (DD)Correspondents

sent by Email “Index” (EE)All

Correspondents sent by Email “Version 1 = 0 to 1000 Pages” (FF)All

Correspondents sent by Email “Version 2 = 1000 to 2000 Pages” (GG)All

Correspondents sent by Email “Version 3 = 2000 to 3000 Pages” (HH)All

Correspondents sent by Email “Version 4 = 3000 to 4000 Pages” (II)All

Correspondents sent by Email “Version 5 = 4000 to 4542 Pages” (JJ)Dentist (A)The 1st

Asbo Folder 1st Index Original https://serverone.hopto.org/1st%20Asbo%20Index%20Orig/

(B)1ST

Asbo Folder “For Magistrates Court Highbury” https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2046/ (C)Asbo “Rip

apart File” https://serverone.hopto.org/Asbo%20Rip%20Apart%201/

(D)The 2nd

Asbo Folder 1st Index Original https://serverone.hopto.org/The%202ND%20Asbo%20Folder%201st%20Index%20Original/

(E)2nd

Asbo Added Bits Only in the Appeal Stage1 https://serverone.hopto.org/2nd%20Asbo%20Added%20Bits%20Only%20In%20the%20Appeal%20Stage1/

(F)2nd

Asbo Folder “For Crown Court Woodgreen” https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2019/ (G)Below

Playground Rip Apart! (H)The

Prosecutions Skeleton Argument No Index /

Not Worth it. (I)The

Prosecutions Skeleton Argument “For the Asbo” https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%208/ (J)My 1st

Asbo Response Bundle INDEX https://serverone.hopto.org/1st%20Asbo%20Responce%20Bundle/

(K)My

Response Bundle “For the Asbo” https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%209/ (L)1st Housing

Possession Order Book INDEX https://serverone.hopto.org/1st%20Housing%20Possession%20Order%20Book%20%20INDEX/

(M)Email Book

Walking to the 1st Housing Possession Order INDEX (N)1st

Possession Order “Dated: 19th July 2017” https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2010/ (O)The

1st Injunction Order INDEX https://serverone.hopto.org/Index%2011/

(P)1st

Injunction Order Statements Getting Ripped https://serverone.hopto.org/1st%20Injunction%20Order%20Statements%20Getting%20Ripped/ (Q)1ST

Injunction Order Dated: 10/08/2017 https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2011/ (R)The

2nd Injunction Order INDEX https://serverone.hopto.org/Index%2012/

(S)The

2nd Injunction Order Statements Getting Ripped https://serverone.hopto.org/The%202nd%20Injunction%20Order%20Statements%20Getting%20Ripped/

(T)2nd

Injunction Order https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2012/ (U)The 2nd

INJUCTION FOLDER INDEXED Original made by Enfield Council When Ordered to by

the Judge Original https://serverone.hopto.org/Index%2013/ (V)All in One

2nd Injunction Order Judge Indexed https://serverone.hopto.org/All%20in%20One%202nd%20Injunction%20Order%20Judge%20Indexed/

(W)2nd

Injunction Order “Indexed by Order of the Judge” https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2013/ (X)A Second

Housing Possession Order Served & Dated: 06/02/2019 Till 10/06/2019 INDEX https://serverone.hopto.org/Index%2015/

(Y)2nd

Possession Order https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2015/ (Z)Freedom

of Information “Enfield Councils Computer System - Index” https://serverone.hopto.org/Enfield%20Councils%20Index/

(AA)Freedom

of Information “Enfield Councils Computer System” https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2016/ (BB)Doctors

NHS & Private “RIO” INDEXED https://serverone.hopto.org/Index%2018/

(CC)Freedom

of Information “NHS Computer System” https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2018/ (DD)Correspondents

sent by Email “Index” https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%200/

(EE)All

Correspondents sent by Email “Version 1 = 0 to 1000 Pages” https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2051/ (FF)All

Correspondents sent by Email “Version 2 = 1000 to 2000 Pages” https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2052/ (GG)All

Correspondents sent by Email “Version 3 = 2000 to 3000 Pages” https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2053/ (HH)All

Correspondents sent by Email “Version 4 = 3000 to 4000 Pages” https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2054/ (II)All

Correspondents sent by Email “Version 5 = 4000 to 4542 Pages” https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2055/ (JJ)Dentist https://serverone.hopto.org/Email%20Book%2017/ (2)

Kidnapping and/or False Imprisonment / Unlawful Detention (a) Kidnapping

and false imprisonment are both common law offences. They are defined in case

law, and not in legislation. (b) Kidnapping

is taking someone away by force or fraud without their consent on any lawful

excuse. (c)

False Imprisonment is detaining someone against

their will (d) Both are

classed as very serious offences, with each carrying the potential for life

imprisonment on conviction. Ø Elements

of the offence In R

v Rahman (1985) 81 Cr App Rep 349 it was held that, on a charge of

false imprisonment, the prosecution must prove: The

unlawful (a) Intentional

behaviour (b) Reckless

behaviour (c) The

restraint of a victim's freedom of movement from a particular place Ø Restraint

of a victim's freedom of movement False

imprisonment at common law involves an act of the defendant which directly

and intentionally (or possibly negligently) causes the confinement of the

claimant within an area delimited by the defendant. Ø The elements

of the existing offence of false imprisonment, as stated above, are that: (a)

D’s conduct results in the restraint of V’s

freedom of movement from a particular place. (b) D intends

the conduct to have this result, or is reckless as to whether it will or not. (c)

The restraint is unlawful, in the sense that it

was without lawful authority or reasonable excuse. (As with kidnapping, a

mistaken belief in the existence of lawful authority or reasonable excuse can

be an excuse in (d) Itself.) Ø

Cooksey [2019] EWCA Crim 1410

where false imprisonment occurred within the context of coercive and

controlling behaviour in a domestic setting. Ø

Ward [2018] EWCA Crim 414

where the court identified aggravating factors for the particular case;

gratuitous degradation of the victim; abuse of power over the victim in his

own home; previous violence or threats towards the victim in the context of a

series of offences; threats made to stop the victim reporting the offending. Ø The

Law Commission (LAW COM No 355) SIMPLIFICATION OF CRIMINAL LAW: KIDNAPPING

AND RELATED OFFENCES (3)

Offences

against the Person Act 1861 s.18 Ø Homicide 4. Conspiring or soliciting to commit murder. Whosoever shall solicit, encourage, persuade, or endeavour to

persuade, or shall propose to any person, to murder any other person, whether

he be a subject of Her Majesty or not, and whether he be within the Queen’s

dominions or not, shall be guilty of a misdemeanour, and being convicted

thereof shall be liable Ø Acts

causing or tending to cause Danger to Life or Bodily Harm 20. Inflicting

bodily injury, with or without weapon. Whosoever

shall unlawfully and maliciously wound or inflict any grievous bodily harm

upon any other person, either with or without any weapon or instrument,

[F2shall be guilty of an offence and liable, on conviction on indictment, to

imprisonment for a term not exceeding 7 years.] Ø

Assaults 42. Persons committing any common assault or battery

may be imprisoned or compelled by two magistrates to pay fine and costs not

exceeding 5 l. Ø Wounding

or grievous bodily harm with intent to cause grievous bodily harm “117

Burncroft Avenue stabbing me with a Knife” because the local Authority’s

allowed them to continue victimising myself. “Section 1 of the

Prevention of Crime Act 1953 prohibits the possession

in any public place of an offensive weapon without lawful authority or

excuse.” Ø Assault

occasioning bodily harm. Whosoever

shall be convicted upon an indictment of any assault occasioning actual

bodily harm shall be liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding 7 years

and whosoever shall be convicted upon an indictment for a common assault

shall be liable, at the discretion of the court, to be imprisoned for any

term not exceeding [two years] Ø What is

the definition of battery in law? Definition.

1. In criminal law, this is a physical act that results in harmful or

offensive contact with another person without that person's consent. 2. In tort law, the intentional causation of harmful or offensive

contact with another's person without that person's consent. Ø How is offensive contact defined? A contact

is offensive within the meaning of § 101(c)(ii) if: 2. (a) The contact is offensive to a reasonable sense of personal dignity;

or. 3. (b) The contact is highly offensive to the other's unusually sensitive. Ø Offences

against the Person Act 1861 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/24-25/100/contents

(4) Ill-treatment

of patients / Mental Health Act 1983 s.127 Ø Understanding

the Laws There

are two specific pieces of legislation that govern how people with mental

health conditions receive care and treatment. They are the Mental

Health Act 1983 (updated by the 2007 Act) and the Mental

Capacity Act 2005, including the Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards. Ø Demeanour

(2) It

shall be an offence for any individual to ill-treat or wilfully to

neglect a mentally disordered patient who is for the time being

subject to his guardianship under this Act or otherwise in his

custody or care (whether by virtue of any legal or moral obligation

or otherwise). Ø Law Ø 127Ill-treatment of patients. (a) It

shall be an offence for any person who is an officer on the staff of or

otherwise employed in, or who is one of the managers of, a hospital [F1,

independent hospital or care home]— (b) To ill-treat

or wilfully to neglect a patient for the time being receiving treatment for

mental disorder as an in-patient in that hospital or home; or (c) To

ill-treat or wilfully to neglect, on the premises of which the hospital or

home form’s part, a patient for the time being receiving such treatment there

as an out-patient. (d) It

shall be an offence for any individual to ill-treat or wilfully to neglect a

mentally disordered patient who is for the time being subject to his

guardianship under this Act or otherwise in his custody or care (whether by

virtue of any legal or moral obligation or otherwise). Ø Penalty (2A)F2. Any

person guilty of an offence under this section shall be liable— (a)

On summary conviction, to

imprisonment for a term not exceeding six months or to a fine not exceeding

the statutory maximum, or to both; (b) On

conviction on indictment, to imprisonment for a term not exceeding [F3five

years] or to a fine of any amount, or to both. Ø Mental

Health Act 1983 s.127 Ø Combo

(Index of Mental Capacity Act 2005 & More.) “Below the audio recorder!”

Ps. It might take a few seconds to load https://www.horrificcorruption.com/doctors

Ø Mental Capacity Act 2005 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/pdfs/ukpga_20050009_en.pdf

(5) Breaches

of the DPA – “Data Protection Act 1998” / GDPR 2016 – “General Data

Protection Regulation” DPA 1998 (a)

Got superseded by the Data Protection

Act 2018 (DPA 2018) on 23 May 2018 (b) Was

a United Kingdom Act of Parliament designed to protect personal data stored

on computers or in an organised paper filing system. It enacted the EU Data

Protection Directive 1995's provisions on the protection, processing and

movement of data. Ø GDPR (a)

The GDPR was adopted on 14 April

2016, and became enforceable beginning 25 May 2018. GDPR will levy harsh

fines against those who violate its privacy and security standards, with

penalties reaching into the tens of millions of euros. Ø The

consequences of breaching the Data Protection Act 1998 / GDPR (b) The

Information Commissioner has the power to issue fines for infringing on data

protection law, including the failure to report a breach. The specific

failure to notify can result in a fine of up to 10 million Euros or 2% of an

organisation's global turnover, referred to as the 'standard maximum. (c)

GDPR is a legal framework that sets

guidelines for the collection and processing of personal information of

individuals within the European Union (EU). It is brought in to UK Law by

means of Part 2 of the DPA 2018 (d) Personal

data is any information relating to an identified or identifiable living

individual. An identifying

characteristic could include a name, ID number or location data. Ø The

GDPR provides the following rights for individuals: (a)

The right to be informed (b) The

right of access (c)

The right to rectification (d) The

right to erasure (e)

The right to restrict processing (f)

The right to data portability (g)

The right to object (h) Rights

in relation to automated decision making and profiling Ø Section

132: Prohibition placed upon the Commissioner, or the Commissioner’s staff

against disclosing information obtained in the course of their role (which is

not available to the public) Section

132 replaces section 59 DPA 1998 and criminalises action by former or current

ICO staff who disclose data obtained during the course of their duties.

Section 132 (2) clarifies the circumstances in which disclosure – with lawful

authority – may be made. Section 132 (3) however confirms that it is an

offence for a person knowingly or recklessly to disclose information in

contravention of subsection (1). Ø Section

144: False statement made in response to an information notice It is an offence for a person, in response to information

notice from the Commissioner, to make or recklessly make, a statement which

they know to be false in a material respect. Ø Section

148: Destroying or falsifying information and documents etc Under Section 148 (2) (a) it is an offence for a

person to destroy or otherwise dispose of, conceal, block or (where relevant)

falsify all or part of the information, document, equipment or material.

Section 148 (2) (b) makes to cause or permit the actions set pout in the

previous subsection. Ø Section

170: Unlawful obtaining etc of personal data Section 170 of the Act builds on section 55 DPA

1998 which criminalised knowingly or recklessly obtaining, disclosing or

procuring personal data without the consent of the data controller, and the

sale or offering for sale of that data. The provision was most

typically/commonly used to prosecute those who had accessed healthcare and

financial records without a legitimate reason. Section 170 adds the offence

of knowingly or recklessly retaining personal data (which may have been

lawfully obtained) without the consent of the data controller. There are some

exceptions: for example, where such obtaining, disclosing, procuring or

retaining was necessary for the purposes of preventing or detecting crime.

Section 170 (2) and (3) set out the defences to Section 170 (1). Ø Section

171: Re-identification of de-identified personal data Section 171 - a new offence - criminalises the

re-identification of personal data that has been ‘de-identified’

(de-identification being a process - such as redactions - to remove/conceal

personal data). Section (5) states that it is an offence for a person

knowingly or recklessly to process personal data that is information that has

been re-identified. Sections 171 (3) and (4) set out the defences to Section

171 (1) – for example, the re-identification was necessary for the purposes

of preventing or detecting crime. Sections 171 (6) and (7) set out the

defences to Section 171 (5). Ø Section

173: Alteration etc of personal data to prevent disclosure to data subject Section 173 relates to the processing of requests

for data from individuals for their personal data. Section 173 (3) makes it a

criminal offence for organisations (persons listed in Section 173 (4)) to

alter, deface, block, erase, destroy or conceal information with the

intention of preventing disclosure. It builds on an offence under the Freedom

of Information Act 2000. Possible defences to an offence under section 173

(3) are set out in Section 173 (5). Ø Section

184: Prohibition of requirement to produce relevant records Section 184 (1) makes it an offence for a person

to require another to provide them with or give them access to a relevant

record linked to the employment, continued employment of one of their

employees or a contract for the provisions of services to them. Section 184

(2) makes it an offence for a person to require another to provide them with

or access to a relevant record if the requestor is involved in the provision

of goods, facilities or services to the public or the requirement is a

condition of providing or offering to provide goods, facilities or services

to the other person or a third party. Section 184 (3) details the possible

defences to offences under subsection 184 (1) or (2). Ø

Data Protection Act 1998 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/29/contents Ø General Data

Protection Regulation 2016 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guide-to-the-general-data-protection-regulation

(6) Freedom

of Information Act 2000 Ø Demeanour (a) The Freedom

of Information Act 2000 provides public access to information held by public

authorities. It does this in two ways: public authorities are obliged to

publish certain information about their activities; and. members of the

public are entitled to request information from public authorities. (b) You

normally have 20 working days to respond to a request. For a request to be

valid under the Freedom of Information Act it must be in writing, but

requesters do not have to mention the Act or direct their request to a

designated member of staff. (c) A

subject access request (SAR) is simply a written request made by or on behalf

of an individual for the information which he or she is entitled to ask for

under section 7 of the Data Protection Act 1998 (DPA). The request does not

have to be in any particular form. Ø Law An

Act to make provision for the disclosure of information held by public

authorities or by persons providing services for them and to amend the Data

Protection Act 1998 and the Public Records Act 1958; and for connected

purposes. Ø Penalty The

penalty is a fine. There are no financial or custodial penalties for failure

to provide information on request or for failure to publish information. But

you could be found in contempt of court for failing to comply with a decision

notice, enforcement notice, or information notice. Ø Freedom

of Information Act 2000 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2000/36/contents

(7) Defamation of Character Act 2013 - “Slander” Ø Demeanour If

lies about you have appeared about you or your business on social media,

a website or in print, or in the case of slander they had been

spoken, and you reasonably believe that your reputation has suffered as a

result, then potentially you are a victim of defamation of character and you

have a claim against the author, the publisher, and anyone else involved in

the publication. Ø Law (a)

The Defamation Act 2013 came into

force on 1 January 2014. (b) Written defamation is called "libel," while spoken

defamation is called "slander." Defamation is not a crime, but it

is a "tort" (a civil wrong, rather than a criminal wrong). A person

who has been defamed can sue the person who did the defaming for damages. (c)

A claimant must satisfy the court

that the defamation is sufficiently serious and that the imputation, extent

and/or nature of the word’s publication is such that real reputational damage

has been suffered. (d) An additional test applies to a body trading for profit, namely a

requirement to show that a statement has caused, or is likely to cause,

serious financial loss. Ø

To prove prima facie defamation, a

plaintiff must show four things: (1) A false statement purporting to be fact; (2) Publication or communication of that statement to a third person; (3) Fault amounting to at least negligence; and (4) Damages, or some harm caused to the person or entity who is the

subject of the statement. Ø To establish a character defamation case, you must show: (a)

The statement was not substantially

true. (b) You can identify who made the false statement. (c)

The person knowingly or recklessly

made a false statement. (d) The statement was published (verbally or in writing) to someone other

than you. (e)

The false statement harmed you. Ø Judgment

in Lachaux -v- Independent Print Ltd [2019] UKSC 27 https://www.hilldickinson.com/insights/articles/defamation-test-serious-harm

(8) Housing

disrepair = (Right to Repair) “UK” Regulations 1994; -- Housing Act 1985 “The

Secure Tenants of Local Housing Authorities” Ø EXPLANATORY

NOTE OF (Right to Repair) “UK” Regulations 1994 (a) These

Regulations give secure tenants of local housing authorities rights relating

to Repairs to their homes which their landlords are obliged, under repairing

covenants, to carry out. Such a tenant is given the right, if the first

contractor does not complete qualifying repairs within specified time limits,

to require the landlord to appoint a second contractor to carry out the

repairs. The tenant is also given a right to compensation from his landlord

if the repairs are not carried out within specified time limits after he has

asked for a second contractor to be appointed. (b) Regulation

2 Contains definitions and provides that landlords

themselves are included in references to contractors in the Regulations. (c) Regulation

3 Describes the circumstances in which the rights apply. A

repair must be within a description of repair prescribed by regulation 4. (d) Regulation

5 Sets out the procedure the landlord should follow if a

tenant asks for a repair to be carried out. If the repair is a qualifying

repair and is not carried out within specified time limits, regulation 6

entitles the tenant to require the landlord to appoint a different contractor

to do the repair. If the repair still is not completed within specified time

limits, the tenant may be entitled to compensation from the landlord under

regulation 7. (e) Regulation

8 Suspends, in exceptional circumstances, the specified

time limits and regulation 11 extends the limits in the transitional cases

described. (f) Regulation

9 Provides that notices may be served by post and regulation

10 provides that disputes may be determined by the county court Ø The

Secure Tenants of Local Housing Authorities (Right to Repair) Regulations

1994 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/1994/133/made

Entitlement

1. 3.—

(1) Subject to and in accordance with these Regulations, secure tenants whose

landlords are local housing authorities are entitled— (a) To

have qualifying repairs carried out, at their landlords' expense, to the

dwelling-houses of which they are such tenants; and (b) To

receive compensation from their landlords if qualifying repairs are not

carried out within a prescribed period. Ø Repair

notice 5.— (1) (b) If the landlord is satisfied that

the repair is not a qualifying repair, it shall notify the tenant of that and

explain why it is so satisfied and give the tenant an explanation of the

provisions of these Regulations; and (c) If the landlord is satisfied that

the repair is a qualifying repair, the landlord shall issue a repair notice

to a contractor and give to the tenant a copy of the notice and an

explanation of the provisions of these Regulations. (2) A repair notice shall contain a

reference sufficient to identify the completed notice and shall specify— (a) The name of the secure tenant; (b) The address of the dwelling-house; (c) The nature of the repair; (d) The name, address and telephone

number of the contractor who is to carry out the repair; (e) The arrangements made for the

contractor to obtain access to the dwelling-house; and (f) The last day of the first prescribed

period. Ø Substitute

Contractor 6.— (1) Subject to paragraph (3) and regulation 8, if— (a) The qualifying repair has not been

carried out within the first prescribed period, and (b) The tenant notifies the landlord that

he requires another contractor to carry out the qualifying repair, the landlord, where it is reasonably practicable,

shall issue a further repair notice to another contractor and give a copy of

the notice to the tenant. (2) The further repair notice shall contain a reference sufficient

to identify it and specify the matters referred to in regulation 5(2)(a) to

(e) and the last day of the second prescribed period. (3) Paragraph (1) does not apply if compliance with that paragraph

would infringe the terms of a guarantee for work done or materials supplied

of which the landlord has the benefit. Ø Compensation 7.— (1) Subject to regulation 8, the landlord shall pay the specified

sum to the secure tenant if the qualifying repair has not been carried out

within the second prescribed period. (2) In paragraph (1), “specified sum” means the lesser of £50 and

£10 + (£2 X n) where N is the number of days (counting part of a day as a

complete day) in the period starting on the day after the second prescribed

period ends and ending on the day on which the qualifying repair is

completed. Ø SCHEDULE

Ø Housing

Act 1985 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1985/68/section/96

(9) Interference with the course of justice 1963 / Perjury

Act 1911 Ø Demeanour

What

is classed as perverting the course of justice? Elements

of the offence of perverting the course of justice (a) Acts

tending (and intended) to obstruct, divert or disrupt criminal proceedings or

police investigations generally may suffice—the offence does not need to have

taken place in respect of a particular trial or investigation. (b) Perverting

the course of justice is a serious criminal offence that can carry a sentence

of up to life in prison and whilst life imprisonment is unlikely,

it is unusual for the court to impose a penalty other than a prison sentence. (c) Obstruction

of justice is an offense that criminalizes any conduct in which a person

wilfully interferes with the orderly administration of justice. Ø What

does it mean to defeat the ends of justice? Definition. Consists in unlawfully and

intentionally engaging in conduct which defeats or. obstructs the course or

administration of justice. Elements. Ø Law (1)

THE LAWCOMMISSION OFFENCES RELATING TO INTERFERENCE WITH THE COURSE OF

JUSTICE

Ø Extract 1.9 (a)

Person should be regarded as intending

a particular result of his conduct if, but only if, either he actually

intends that result or he has no substantial doubt that the conduct will have

that result; (b) A

person should be regarded as knowing that a particular circumstance exists

if, but only if, either he actually knows or he has no substantial doubt that

that circumstance exists; (c)

A person should be regarded as being

reckless as to whether a particular circumstance exists if, but only if, (i) he realises at the time of that conduct that there is

a risk of that circumstance existing and (ii) it is unreasonable for him to

take that risk. The question whether it is unreasonable for him to take the

risk is to be answered by an objective assessment of his conduct in the light

of all relevant factors, but on the assumption that any judgment he may have

formed of the degree of risk was correct. PART II: PERJURY Ø PRESENT LAW AND WORKING PAPER PROPOSALS (2)

The present law as to perjury in

judicial proceedings is to be found in the Perjury Act 1911 (hereafter

"the 1911 Act"). Section I of the Act provides that if a person

lawfully sworn as a witness or interpreter in a judicial proceeding wilfully

makes a statement material in that proceeding which he knows to be false or

does not believe to be true he shall be guilty of perjury. By virtue of

section 1(5) the offence extends to such statements made by persons lawfully

sworn under the authority of an Act of Parliament (a) In

any part of H.M.'s dominions or (b) Before

a British tribunal or officer in a foreign country. Certain statements not

made before a court are by section 1(3) treated as being made in judicial proceedings. 2.2 The 1911 Act deals not only with

perjury in judicial proceedings but also with statements on oath otherwise

than in judicial proceedings (a)

(section 2),

False oaths or statements with reference to marriage (b) (section

3), False declarations or statements in relation to

births and deaths (c)

(section 4),

False statutory declarations and other oral declarations required under an

Act of Parliament (d) (section

5), And false declarations to obtain registration

for carrying on a vocation (e)

(section 6).

Finally, (f)

(section 7(1)

Deals with aiding, abetting or suborning a person to commit an offence under

the Act and section 7(2) with inciting or attempting to procure or

suborn a person to commit an offence under the Act. Subornation is no more

than another name for procuring an offence, whilst the other ancillary offences

in this section add nothing to the general law to be found in section 8 of

the Accessories and Abettors Act 1861 and the common law. Also

see (10)

(2) Public Justice Offences

incorporating the Charging Standard https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/public-justice-offences-incorporating-charging-standard

Ø Extract AAAA (11)

Disclosure Procedure and Investigations Act 1996 (CPIA) Ø Demeanour

“Fairness

ordinarily requires that any material held by the prosecution which weakens

its case or strengthens that of the defendant, if not relied on as part of

its formal case against the defendant, should be disclosed to the defence.

Bitter experience has shown that miscarriages of justice may occur where such

material is withheld from disclosure. The golden rule is that full disclosure

of such material should be made.” (R v H [2004] UKHL 3; [2004] 2 Cr.

App. R. 10, House of Lords). Ø The Law on Disclosure is found here The Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act 1996 (CPIA) Part I Disclosure and Part II Criminal Investigations contains the main statutory disclosure provisions. Additional guidance for the proper disclosure of unused material can

be found in: (a)

CPIA Code of Practice, issued under s.23 CPIA (the Code of Practice); (b) Judicial Protocol on the Disclosure

of Unused Material in Criminal Cases (the Judicial Protocol); (c)

Attorney-General’s Guidelines on

Disclosure - For Investigators, Prosecutors and Defence Practitioners

(the A-G’s Guidelines); (d) Criminal Procedure Rules (Crim PR)

Part 15. (e)

Protocol and Good Practice Model on

the Disclosure of Information in cases of Alleged Child Abuse and linked

Criminal and Care Directions (the Child Abuse Protocol) (f)

The Better Case Management (BCM)

Handbook (the BCM Handbook) - in particular paragraph 3.20 Ø The Duty to Disclose Commences when: -- The statutory duty under the CPIA commences once the defendant (in the

Magistrates’ Court) has pleaded not guilty and the case has been adjourned

for trial or (for cases going to the Crown Court) once the case has been sent

for trial to the Crown Court (see s.1 CPIA). It lasts until the end of the trial (see s.7A CPIA; R (on the

application of Nunn) v Chief Constable of Suffolk Constabulary and another

[2014] UKSC 37; [2014] 2 Cr. App. R. 22; [2015] Crim. L.R. 76;

see also section 7 of the Code of Practice). Before this time there is a common law duty of disclosure requiring

the prosecution to disclose material reasonably thought capable of assisting

a defendant, for example in bail applications or where it would be helpful in

allowing a defendant to prepare his case. Ø Disclosure

under “Abuse

of Process.” https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/abuse-process

Non-disclosure by

prosecutor Failure on the part of the prosecution to comply

with its disclosure obligations may amount to an abuse of process. Some of the relevant factors to be taken into

account when deciding whether non-disclosure amounts to abuse of process were

considered in Salt [2015] 1 WLR 4905. They included: (a) The

gravity of the charges; (b) The

denial of justice to the complainants; (c) The

necessity for proper attention to be paid to disclosure, the nature and

materiality of the failures; (d) The

conduct of the defence; (e) The

waste of court resources; (f) The

effect on the jury; (g)

The availability of sanctions other than halting proceedings. However, in DPP v Petrie [2015]

EWHC 48 (Admin), it was noted that in some cases: “A wholesale failure on

the part of the prosecution to comply with its disclosure obligations may

require the prosecution to offer no evidence, in accordance with the

professional code for prosecutors and the guidance set out in the CPS/ACPO

Disclosure Manual”. “The possibility of such

an outcome serves to illuminate that only rarely will recourse to an abuse of

process argument be necessary or appropriate”. However, see the section

on Prosecution Failures, later in this guidance. (12)

Abuse of Process / Malicious

Prosecution Ø Demeanour

What

is the difference between abuse of process and malicious prosecution? The

primary difference between the two legal actions is

that malicious prosecution concerns

the malicious or wrongful commencement of an action,

while, on the other hand, abuse of process concerns the improper

use of the legal process after process has already been

issued and a suit has commenced. Ø Law (1) Abuse

of process has been defined as "something so unfair and wrong that the

court should not allow a prosecutor to proceed with what is in all other

respect a regular proceeding" (2) Both

the Crown Courts and magistrates' courts have discretion to protect the

process of the court from abuse. This includes protecting the accused person

from oppression or prejudice. The courts have often emphasised that the power

to stay a case for an abuse of process is an exceptional power to be

exercised sparingly A

case might form an abuse of process where: (a) The

defendant would not receive a fair trial; and/or (b) It

would be unfair for the defendant to be tried. (3) The

traditional view has been that the burden of proof is on the defence to show

that the proceedings should be stayed as an abuse of process. The standard of

proof is the balance of probabilities. However, the decision to stay

proceedings as an abuse of process is an exercise in judicial assessment

based on judgment, rather than on any conclusion as to fact based on

evidence, and use of terms such as 'burden of proof' and 'standard of proof'

has the potential to mislead (4) There

is no exhaustive list of situations where a court might halt a case for an

abuse of process but the specific categories below are the most common

situations where arguments arise. (1) R v Derby Crown Court ex p Brooks: “It may be an abuse of process if

either (a)

The

prosecution has manipulated or misused the process of the court so as to

deprive the defendant of a protection provided by law or to take unfair

advantage of a technicality, or (b) On the balance of probability, the

defendant has been, or will be, prejudiced in the preparation or conduct of

his defence by delay on the part of the prosecution which is unjustifiable”

“The ultimate objective of this discretionary power is to ensure that there

should be a fair trial according to law, which involves fairness both to the

defendant and the prosecution ….” (2) R v Martin (Alan): „No single formulation will readily

cover all cases, but there must be something so gravely wrong as to make it

unconscionable that a trial should go forward, such as some fundamental

disregard for basic human rights or some gross neglect of the elementary

principles of fairness. ‟ Ø Two

Categories of Abuse In

considering the development of case law it is clear that the Higher Courts

will sometimes use the abuse of process jurisdiction to effectively ‘punish’

the police or prosecution for errors or faults. This ‘serious fault’ limb of

the abuse of process jurisdiction highlights the way abuse applications fall

into two broad categories; (a)

Category 1

cases where the defendant cannot receive a fair trial, and (b) Category

2 cases where it would be unfair for the defendant to be

tried: see R v Beckford (1996) 1 Cr App R 94, 101. Thus, if

evidence that should have been seized by the police but now cannot be

obtained, but would have been helpful to the defence, then that is a

‘Category 1’ situation and the Judge could, exceptionally, stay the trial on

the basis that the defendant could not get a fair trial. Ø

If, however, the police had the

material but maliciously destroyed it, then that would be a ‘Category 2’ case

and even though the defendant could get a fair trial it would be unfair to

try him – in as much as it would offend our sense of justice and bring the

administration of the criminal justice system into disrepute to do so, see

e.g., R v Mullen [1999] 1 AC 42, HL. Ø Abuse

of Process https://www.cps.gov.uk/legal-guidance/abuse-process

Ø Lawsuits

for Malicious Prosecution or Abuse of Process (13)

Criminal damage Act 1971 Ø Demeanour

The

offence of criminal damage is committed when a person destroys

or damages property belonging to another person without lawful

excuse, in contravention of the Criminal Damage Act 1971.

The damage caused as a result of the offence does not have to be

permanent. Ø Law Other than Aggravated Criminal Damage) (a) Section

1(1) Criminal Damage Act 1971 - A person who without lawful excuse destroys

or damages any property belonging to another, intending to destroy or damage

any such property, or being reckless as to whether any such property would be

destroyed or damaged, shall be guilty of an offence. Ø Aggravated

Criminal Damage and Aggravated Arson (a) Aggravated

criminal damage is set out at s.1(2) and aggravated arson is at s.1(2) and

(3) Criminal Damage Act 1971. The aggravated offences require proof of an

intent to destroy or damage any property or being reckless as to whether any

property would be destroyed or damaged; and intending by the destruction or

damage to endanger the life of another or being reckless as to whether the

life of another would be thereby endangered. (b) Section

4 Criminal Damage Act 1971 sets out a maximum penalty of life imprisonment

for aggravated criminal damage and aggravated arson. The offences are only

triable on indictment. (c) If

the damage is committed by fire, the offence is charged as arson with intent

or being reckless as to whether the life of another would be thereby

endangered. (d) Where

the aggravated form of damaging property/arson is charged, specific counts

should be preferred, as follows: (e) Intending

to destroy/damage property or being reckless as to whether property would be

destroyed/damaged and intending to endanger the life of another; or (f) Intending

to destroy/damage property or being reckless as to whether property would be

destroyed/damaged and being reckless as to whether life would be endangered. Ø

See

further R

v Hoof (1981) 72 Cr App R 126 and R v Hardie (1984) 3 All ER 848. Although both cases

involved arson, the comments on charging practice are equally applicable

where the damage is caused other than by fire. Ø Penalty

4

Punishment of offences. (a)

A person guilty of arson under

section 1 above or of an offence under section 1(2) above (whether arson or

not) shall on conviction on indictment be liable to imprisonment for life. (b) A

person guilty of any other offence under this Act shall on conviction on

indictment be liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding ten years. Ø Criminal

damage Act 1971 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1971/48/pdfs/ukpga_19710048_en.pdf

(14)

Discrimination = Race relations Act

1976 (Repealed) Race relations Act 2000 / to the Equality Act 2010 Ø Demeanour (a)

The Act banned racial discrimination in public places and made the promotion of

hatred on the grounds of 'colour, race, or ethnic or national origins' an offence. (b) It requires all public functions to be

carried on without racial discrimination and imposes on

certain specified bodies general and specific duties to promote racial equality. It also gives the Commission of Racial Equality (“CRE”) enhanced powers to issue statutory

guidance and enforce the specific duties Ø Category (a)

Racially-aggravated assault (b) Racially-aggravated

criminal damage (c)

Racially-aggravated

harassment/putting another in fear of violence (d) Racially-aggravated

public order offence Ø Law 1.

Racial discrimination (1)

A person discriminates against another

in any circumstances relevant for the purposes of any provision of this Act

if— (a)

On racial grounds he treats that

other less favourably than he treats or would treat other persons; or (b) He

applies to that other a requirement or condition which he applies or would

apply equally to persons not of the same racial group as that other but— (I)

Which is such that the proportion of

persons of the same racial group as that other who can comply with it is

considerably smaller than the proportion of persons not of that racial group

who can comply with it: and (II)

Which he cannot show to be

justifiable irrespective of the colour, race, nationality or ethnic or

national origins of the person to whom it is applied; and (III)

Which is to the detriment of that

other because he cannot comply with it. (2)

It is hereby declared that, for the

purposes of this Act, segregating a person from other persons on racial

grounds is treating him less favourably than they are treated. 2.

Discrimination by way of

victimisation (1)

A person (" the discriminator

") discriminates against another person (" the person victimised

") in any circumstances relevant for the purposes of any provision of

this Act if he treats the person victimised less favourably than in those

circumstances he treats or would treat other persons, and does so by reason

that the person victimised has— (a)

Brought proceedings against the

discriminator or any other person under this Act; or (b) Given

evidence or information in connection with proceedings brought by any person

against the discriminator or any other person under this Act; or (c)

Otherwise done anything under or by

reference to this Act in relation to the discriminator or any other person;

or (d) Illegal

that the discriminator or any other person has committed an act which

(whether or not the allegation so states) would amount to a contravention of

this Act, (e)

or by reason that the discriminator

knows that the person victimised intends to do any of those things, or

suspects that the person victimised has done, or intends to do, any of them. (2)

Subsection (1) does not apply to

treatment of a person by reason of any allegation made by him if the

allegation was false and not made in good faith. 3.

Meaning of " racial

grounds", " racial group " etc. (1)

In this Act, unless the context

otherwise requires— ·

" Racial grounds " means

any of the following grounds, namely colour, race, nationality or ethnic or

national origins; ·

" Racial group " means a

group of persons defined by reference to colour, race, nationality or ethnic

or national origins, and references to a person's racial group refer to any

racial group into which he falls. (2)

The fact that a racial group

comprises two or more distinct racial groups does not prevent it from

constituting a particular racial group for the purposes of this Act. (3)

In this Act— (1)

References to discrimination refer to

any discrimination falling within section 1 or 2; and (2)

References to racial discrimination refer

to any discrimination falling within section 1, and related expressions shall

be construed accordingly. (4)

A comparison of the case of a person

of a particular racial group with that of a person not of that group under

section 1(1) must be such that the relevant circumstances in the one case are

the same, or not materially different, in the other. 29. Discriminatory

advertisements (1)

It is unlawful to publish or to cause

to be published an advertisement which indicates, or might reasonably be

understood as indicating, an intention by a person to do an act of

discrimination, whether the doing of that act by him would be lawful or, by

virtue of Part II or III, unlawful. (2)

Subsection (1) does not apply to an

advertisement— (a)

if the intended act would be lawful

by virtue of any of sections 5, 6, 7(3) and (4), 10(3), 26, 34(2)(b), 35 to

39 and 41; or (b) if

the advertisement relates to the services of an employment agency (within the

meaning of section 14(1)) and the intended act only concerns employment which

the employer could by virtue of section 5, 6 or 7(3) or (4) lawfully refuse

to offer to persons against whom the advertisement indicates an intention to

discriminate. (3)

Subsection (1) does not apply to an

advertisement which indicates that persons of any class defined otherwise

than by reference to colour, race or ethnic or national origins are required

for employment outside Great Britain. (4)

The publisher of an advertisement made

unlawful by subsection (1) shall not be subject to any liability under that

subsection in respect of the publication of the advertisement if he proves— (a)

that the advertisement was published

in reliance on a statement made to him by the person who caused it to be

published to the effect that, by reason of the operation of subsection (2) or

(3), the publication would not be unlawful; and (b) that

it was reasonable for him to rely on the statement. (5)

A person who knowingly or recklessly

makes a statement such as is mentioned in subsection (4)(a) which in a

material respect is false or misleading commits an offence, and shall be

liable on summary conviction to a fine not exceeding £400. 32. Liability

of employers and principals (1)

Anything done by a person in the

course of his employment shall be treated for the purposes of this Act

(except as regards offences thereunder) as done by his employer as well as by

him, whether or not it was done with the employer's knowledge or approval. (2)

Anything done by a person as agent

for another person with the authority (whether express or implied, and

whether precedent or subsequent) of that other person shall be treated for

the purposes of this Act (except as regards offences thereunder) as done by

that other person as well as by him. (3)

In proceedings brought under this Act

against any person in respect of an act alleged to have been done by an

employee of his it shall be a defence for that person to prove that he took

such steps as were reasonably practicable to prevent the employee from doing

that act, or from doing in the course of his employment acts of that

description. 48. Power

to conduct formal investigations (1)

Without prejudice to their general

power to do anything requisite for the performance of their duties under

section 43(1), the Commission may if they think fit, and shall if required by

the Secretary of State, conduct a formal investigation for any purpose

connected with the carrying out of those duties. (2)

The Commission may, with the approval

of the Secretary of State, appoint, on a full-time or part-time basis, one or

more individuals as additional Commissioners for the purposes of a formal

investigation. (3)

The Commission may nominate one or

more Commissioners, with or without one or more additional Commissioners, to

conduct a formal investigation on their behalf, and may delegate any of their

functions in relation to the investigation to the persons so nominated. Ø Penalty

Maximum sentence and racially and/or

religiously aggravated assaults

Common

assault, battery and offences contrary to sections 47 and 20 OAPA are capable

of being charged as racially and/or religiously aggravated assaults, where

the provisions of s.28 Crime and Disorder Act 1998 are met. This results in a

different sentencing framework, as follows:

Ø Race relations Act 2000 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1976/74/enacted Ø Statutory CODE OF PRACTICE ON RACIAL

EQUALITY IN EMPLOYMENT Ø Equality

Act 2010: guidance https://www.gov.uk/guidance/equality-act-2010-guidance As

you grow up, you may see racism, you may have racist things happen to you or

to people you care about. It is important to know what racism is and what to

do about it because no one should be treated badly because of how they look,

the language they speak or where their family is from. Samir Jeraj, Race Equality Foundation (15)

Violent

Disorder Public Order Act 1986 s.2 Ø Demeanour Violent Disorder (a)

Where

3 or more persons who are present together use or threaten unlawful violence and the conduct

of them (taken together) is such as would cause a person of reasonable

firmness present at the scene to fear for their personal safety, each of the

persons using or threatening unlawful violence is guilty of violent (b) Section 3

of the Public Order Offences Act 1986, affray is a criminal

offence, committed when someone threatens violence toward another person, and

behaves in such a manner that other people are fearful of their personal

safety. (c)

Section

4 of the Public Order Act. This offence is referred to as Threatening Behaviour or intending

to cause someone to fear or to provoke violence. Ø Public Order Offences Ø Law \18 Use of words or behaviour or display of

written material. (1) A person who uses threatening, abusive or insulting words or

behaviour, or displays any written material which is threatening, abusive or

insulting, is guilty of an offence if— (a)

He intends thereby to stir up

racial hatred, or (b)

Having regard to all the circumstances

racial hatred is likely to be stirred up thereby. (2) An offence under this section may be committed in a public or a

private place, except that no offence is committed where the words or

behaviour are used, or the written material is displayed, by a person inside

a dwelling and are not heard or seen except by other persons in that or

another dwelling. Ø 19 Publishing or distributing written material. (1) A person who publishes or distributes written material which is

threatening, abusive or insulting is guilty of an offence if— (a)

He intends thereby to stir up

racial hatred, or (b)

Having reg Ø 20 Public performance of play. (1) If a public performance of a play is given which involves the use of

threatening, abusive or insulting words or behaviour, any person who presents

or directs the performance is guilty of an offence if— (a) He intends thereby to stir up racial hatred, or (b) Having regard to all the circumstances (and, in particular, taking Ø 21

Distributing, showing or playing a recording. (1) A

person who distributes, or shows or plays, a recording of visual images or

sounds which are threatening, abusive or insulting is guilty of an offence

if— (a) He intends thereby to stir up racial

hatred, or (b) Having regard to all the

circumstances racial hatred is likely to be stirred up thereby. (2) In

this Part “recording” means any record from which visual images or sounds

may, by any means, be reproduced; and references to the distribution, showing

or playing of a recording are to its distribution, showing or playing of a

recording are to its distribution, showing or playing to the public or a

section of the public. (3) In

proceedings for an offence under this section it is a defence for an accused

who is not shown to have intended to stir up racial hatred to prove that he

was not aware of the content of the recording and did not suspect, and had no

reason to suspect, that it was threatening, abusive or insulting. (4) This section does not apply to the

showing or playing of a recording solely for the purpose of enabling the

recording to be included in a programme service]. Ø 22

Broadcasting or including programme in cable programme service. (1) If

a programme involving threatening, abusive or insulting visual images or sounds

is included in a programme service], each of the persons mentioned in

subsection (2) is guilty of an offence if— (a) He intends thereby to stir up racial

hatred, or (b) Having regard to all the

circumstances racial hatred is likely to be stirred up thereby. (2) The persons are— (a) The person providing the programme

service, (b) Any person by whom the programme is

produced or directed, and (c) Any person by whom offending words

or behaviour are used. (2) If

the person providing the service, or a person by whom the programme was

produced or directed, is not shown to have intended to stir up racial hatred,

it is a defence for him to prove that— (a) He

did not know and had no reason to suspect that the programme would involve

the offending material, and (b) Having

regard to the circumstances in which the programme was included in a

programme service], it was not reasonably practicable for him to secure the

removal of the material. (4) It

is a defence for a person by whom the programme was produced or directed who

is not shown to have intended to stir up racial hatred to prove that he did

not know and had no reason to suspect— (a) That the programme would be included

in a programme service], or (b) That the circumstances in which the

programme would be . . . F8so included would be such that racial hatred would

be likely to be stirred up. Ø Penalty

Ø Public

Order Act 1986 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1986/64/section/18?view=plain

Ø Public

Order Act 1986 CHAPTER 64 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1986/64/enacted/data.xht?view=snippet&wrap=true (16)

Harassment and Stalking 1997 Ø Demeanour Harassment

and stalking are classed as offences under the Protection from Harassment Act

1997 and (where the offending is racially or religiously aggravated) the

Crime and Disorder Act 1998. Both offences relate to behaviour that is

repeated and unwanted. Harassment

is behaviour intended to cause a person alarm or distress. The behaviour must

occur on more than one occasion but it does not have the be the same kind of

behaviour on each occasion. Common harassment incidents include: (a)

Texts, voicemails, letters or emails (b) Comments

or threats (c)

Standing outside someone’s house or driving past

it Ø

Harassment involving putting people in fear of violence is a

more serious offence. It involves two or more harassment incidents that leave

the victim fearing that violence will be used against them. Ø

Stalking involves persistently following someone. It does

not necessarily mean following them in person and can include watching,

spying or forcing contact with the victim through any means, including

through social media. Stalking involving

fear of violence or serious alarm or distress is a more serious offence. It

involves two or more occasions that have caused the victim to fear violence

will be used against them or had a substantial adverse effect on their

day-to-day activities, even where the fear is not explicitly of violence.

Evidence that the stalking has caused this level of fear could include the

victim: (a)

Changing their route to work, work patterns or

employment to avoid contact with the stalker (b) Putting

additional home security measures in place (c)

Moving home (d) Suffering

physical or mental ill-health For both

harassment and stalking, the offence is more serious if it is racially or

religiously motivated, that is carried out because of someone’s racial or

ethnic origin or their religion or lack of religion. Ø Sentencing Parliament

sets the maximum (and sometimes minimum) penalty for any offence. When

deciding the appropriate sentence, the court must follow any relevant

sentencing guidelines, unless it is not in the interests of justice to do so. Ø Penalty What is

the maximum sentence for harassment or stalking? Ø If the

offence is harassment or stalking: (a)

The maximum sentence is six months’ custody (b) If